As I anticipated in the last blog post, today we’ll talk about function composition. It’s a concept I’m very familiar with since it actually belongs to Mathematics! It refers to the action of composing multiple functions together, in order to create a new function. There are of course some conditions that you need to verify first, before trying to compose two or more functions together. In Mathematics you need to make sure that domain and codomain are properly correlated for each couple of the chain, meaning that the inner function’s codomain needs to be included in the outer function’s domain. Otherwise, you might end up trying to analyze the behavior of a function in a point that doesn’t even belong to the function’s domain, probably leading you to a mistake but most certainly making you waste time. There are ways around these issues, like using domain restrictions, but I think that enough for now! After all, the scope is still JavaScript right?!

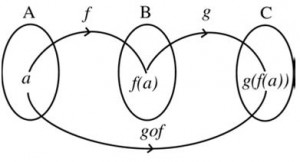

Before starting to describe how function composition found its place in computer science and why should we use it, let’s see visually what we talked about:

The empty circle in between the functions is the symbol representing composition. You should definitely be aware that writing f ○ g and g ○ f, produces in general two very distinct results, admitted that the composition is possible both ways!

Now, the same general concept can be applied to the context of Computer Science. You can build a single compose function that takes in multiple functions and, following a certain order of execution, makes sure that every function of the chain gets called with the return value of the function preceding it. As you probably already figured out, there are a few things we need to be careful about:

-

We need to make sure that the return value of each function in the chain (besides the last to be evaluated) is actually a valid input for the next function. So as you can see before we had to keep an eye on domain and codomain, while now we have a potential issue with data types!

-

All this also means that the functions that we’re trying to compose together should be as simple and predictable as possible. Our job is to assemble them into more a more complex chain of operations, not to get lost in all the return values and data types involved in a single complex function. Therefore, an ideal candidate is a function that takes one input and one output, being therefore easily testable and having predictable behavior!

If only we knew a way to make our functions simpler and composable… Oh wait, we actually do! We talked about currying before, so if you remember we can curry our functions making sure we break them down into smaller functions. These functions have an arity of 1 and no side-effects, making your “quality check” at point one way easier!

//A simple classic example in ES6

const add3Numbers = (a, b, c) => a + b + c;

//This function receives three arguments with data type Number, and returns their sum. Let's curry this function:

const curryAdd3 = a => b => c => a + b + c;

Check out last week’s article to read more about currying and partial application.

Before we actually dive into a nice practical example, let’s take a couple minutes to talk about how to compose multiple functions together. You probably found yourself doing this into your code, or simply into your mind, many times:

const result = myFunction(myOtherFunction(data));

//Let's see a specific example

const add10 = x => x + 10;

const squareIt = x => x * x;

const result = squareIt(add10(7));

console.log(result) // 289

This is, of course, one way of composing functions together. Notice that, differently from higher order functions, here our outer function squareIt takes the return value of add10() not the function itself. Now, assume we need to compose a long list of functions. It becomes clear right away that we need a better way to build our pipeline, a way that makes our intentions and our code clear and readable.

Assuming we have a list of composable functions, where all the hypotheses we made before are respected, there are some external libraries on the market that we can use to have some solid and production-ready functions. Lodash/fp (fp stands for Functional Programming), Underscore, Ramda and others, offer an implementation of the compose() function. As I mentioned last time, I will get into the details of each of them into a separate article, but it’s good to know that we can always code the compose function ourselves! After all, those are just libraries… That means that a bunch of generous and passionate people had the brilliant idea of making our lives easier, powering us up with some extra functionality ready to for use.

Lets take a look at how to code our own compose function:

const compose = (...functions) => data => functions.reduceRight((value, func) => func(value), data);

This compose function is a high order function, as it takes an array of functions as argument and applies reduceRight on those functions in order to return another function. Each future function will be called with the return value of the current function invoked with the current argument. The signature of this function is, therefore:

compose(function1, function2, ... , functionN): Function

So here we’re using reduceRight, meaning that the order of execution is right-to-left or bottom-to-top. This is a detail to always keep in mind when you order your functions inside the compose() function! You might be wondering why do we have to follow this order of operation? Well, for those of you who prefer following a left-to-right or top-to-bottom order of operations there’s pipe().

It’s easy to provide our own implementation for the pipe function:

const pipe = (...functions) => data => functions.reduce((value, func) => func(value), data);

The only difference here is that we’re using reduce() instead of reduceRight(), changing the order of composition to left-to-right. We can find an implementation in Ramda that:

Performs left-to-right function composition. The leftmost function may have any arity; the remaining functions must be unary.

Let’s sum it all up with a nice example! Let’s say we have a list of people, each individual has some properties and we need to do some operations based on those properties. For our demographic statistics, we’ll be studying how many liters of alcohol does, on an average, a member of our group consumesin a week. We’ll also be targeting a specific spectrum of our champion, all those whose age is over 40. Then we’ll use the avarage value to do some calculations!

const list = [{ name: "John Atkins", age: 18, listersOfAlcohol: 8 }, { name: "Jane Barker", age: 68, listersOfAlcohol: 2}, {name: "James Cruels", age: 51, listersOfAlcohol: 15}, {name: "Jyde Derril", age: 37, listersOfAlcohol: 7}, {name: "Joseph Engress", age: 88, listersOfAlcohol: 5}, {name: "Jared Feurmann", age: 42, listersOfAlcohol: 18}, {name: "Jason Granger", age: 27, listersOfAlcohol: 3}];

//Let's build some functions that we'll be using in our pipe

const over40 = object => object.filter(person => person.age > 40);

const liters = object => object.map(person => person.listersOfAlcohol);

const avgWeeklyLiters = array => array.reduce((total, liters) => total + liters) / array.length;

const yearlyDrinks = amount => Math.round( amount * 52,1429);

const message = amount => console.log(`Our study showed that a subject over 40 y.o. in our group drinks on average ${amount} L of alcohol yearly`);

pipe(

over40,

liters,

avgWeeklyLiters,

yearlyDrinks,

message

)(list)

// "Our study showed that a person over 40 y.o. in our group drink on average 520 L of alcohol yearly"

If we tried using compose without altering the order like this:

compose(

over40,

liters,

avgWeeklyLiters,

yearlyDrinks,

message

)(list)

//NaN

Then we would get an error because our chain of commands starts from the bottom! Considering how we defined the order, message() would still be invoked without problems since the input is simply interpolated. When we get to yearlyDrinks() though, we’re expecting our data type to be Number, not String and we will see the “NaN” error printed out!

Let’s redefine the order:

compose(

message,

yearlyDrinks,

avgWeeklyLiters,

liters,

over40

)(list)

//"Our study showed that a person over 40 y.o. in our group drink on average 520 L of alcohol yearly"

In conclusion, you can use whatever order you prefer or think might be best for the specific case you’re testing. The only important thing to do is to always follow the flow of inputs/outputs of your functions! There are of course many practical ways where you’ll want to use function composition, my examples just scratched the surface of the magic you can achieve with it!

Get your hands dirty and try your own examples, see you next week!